TRANSCRIPT

INTRODUCTION

I'm Marty Stouffer. The Dakota Indians called this area "Maco Sica", meaning a bad land. French Trappers called it "A bad land to cross." Today, we call it Badlands National Park. From a human perspective it may indeed be a bad place, dry and desolate, with eroded canyons that from a natural maze of enormous complexity. But for the animals that live here there is nothing bad about it at all, for them "the Badlands" are home.

Isolated and protected within the steep canyons, pieces of prairie have been preserved. Each is small, but combined they form our largest mixed grass prairie ecosystem. Let's meet the animals that live here, in the "BADLANDS."

TRANSITION TO TITLE / BADLANDS NATIONAL PARK, SOUTH DAKOTA

Dawn on the prairie is a particularly active time for wildlife. As the temperature rises, Mule Deer follow the shadows into the deep, cool canyons.

TURKEY VULTURES SOARING

Turkey Vultures spread their wings to absorb warmth from the early morning sun. They wait patiently for the thermals that will allow them to survey their domain.

SUPERIMPOSED MAP OF SOUTH DAKOTA

South Dakota is home to some of our lushest, most fertile prairie soils. Most of this land has been converted to farms and ranches. But one particularly rugged area has not been settled and is now preserved within Badlands National Park. Two-hundred and forty-four thousand acres are home for a variety of wildlife.

It's an enchanted land, scoured and sculpted by water a fraction of an inch at a time. It was water that deposited these sediments about 30 million years ago, and it is water today which slowly, but inevitably, carries this sediment back to the sea. Each year erosion reveals new secrets locked for millennia within the soil.

This area contains one of the richest deposits of mammal fossils found anywhere in the world.

FOSSIL OF HYRACONDON / SABER-TOOTHED CAT

30 million year old specimens, like this Hyracodon, were followed later by mammoths, camels, and a host of other grazing animals.

An equally impressive array of predators, such as this Saber-Toothed Cat, hunted the grazing animals.

All of these species became extinct or evolved into new forms, but their fossil bones played an important role in establishing the park and protecting the animals which live here today.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN BIGHORN SHEEP

Bighorn Sheep are well suited to a life on the sheer ridges. In fact, most of the time they remain near steep slopes where safety is only a few bounds away.

These Rocky Mountain Bighorn were introduced into the park in 1967. The native Audubon Bighorn, a slightly different sub-species, were exterminated by early settlers at the turn of the century. Grizzly Bears, Bison, Wolves, and Elk all became locally extinct soon after the arrival of hunters and homesteaders.

TRANSITION TO OLD SETTLER'S HOME

But life was not easy for the settlers either. Cold Winters, hot Summers, and lack of moisture drove many away. As they left, wildlife began to recover. Many of the species originally present have since recolonized the area, or have been reintroduced. Once again the Badlands belong to wildlife.

PRAIRIE DOGS

When our ancestors moved west, Prairie Dog towns blanketed much of our grassland. One town was said to be 100 miles wide and 250 miles long, containing perhaps 400 million of the plump rodents.

When cattle arrived, Prairie Dogs were viewed as competitors. They were shot, poisoned, and trapped from most of their former range. Towns in this park, and in other areas, have since recuperated.

Prairie Dogs play a critical ecological role on the grasslands. Their digging helps aerate the soil, and their burrows provide a year round refuge for many other small mammals, reptiles, and insects.

Trimming the vegetation close to the ground may be a rancher's nightmare, but to the Prairie Dogs, it makes good sense. This strategy ensures a constant supply of fresh green shoots as well as better visibility of predators.

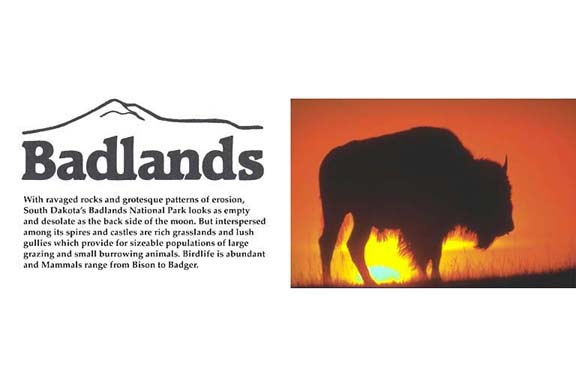

BISON

Bison also enjoy the fresh shoots on the Prairie Dog towns. Unlike cattle, Bison and Prairie Dogs have peacefully coexisted for thousands of years.

In the eighteen hundreds, hunters reduced the great herds of Bison from an estimated sixty-five million to a mere one thousand. Bison disappeared completely from the Badlands. They were shot primarily for their meat and hides, but their extermination was also part of a larger strategy to eliminate the Indian's food supply and force them onto reservations.

A small group of Bison was reintroduced into the park in 1963. Today, there are about five hundred here, and their future seems secure.

BISON RUTTING SEASON / COURTING

By mid-summer the tempo in the Bison herd is increasing rapidly. Bulls, which are solitary most of the year, join the cows. This congregation marks the beginning of the rut.

Bulls fight for the right to tend a female in estrus. Often a cow will be pursued by a large group of eager bulls. They may chase her for miles in one hundred degree temperatures. It seems like a costly method of reproduction, yet it ensures that the strongest bulls breed most of the cows.

By August the land becomes parched and dry. Small steams and ponds gradually disappear, forcing the animals to move to new areas.

TIME-LAPSE OF MUD DRYING / CRACKING / BIGHORN CARCASS

Most animals are well adapted to the scorching temperatures and lack of water.

This Bighorn ram was probably weakened by disease. Nature selects only the healthiest to survive and reproduce.

One reason that humans did not remain in this area is the lack of good water. Most of the surface water is muddy and unfit for either drinking or agriculture. One frustrated settler termed it "Too thick to drink and too thin to plow." It seems to suit the Killdeer just fine.

Temperatures can exceed one-hundred degrees for several months, so the few remaining water holes get plenty of visitors.

TIME-LAPSE SUNSET / TRANSITION TO SNOW FALL IN AUTUMN

The cool days of Autumn are followed by the first snows of Winter.

By late November, Bighorn Sheep gather for their rut.

BIGHORN RAMS BUTTING HEADS / SLOW-MOTION

Rams join into groups, sizing each other up with ritualized displays. This behavior establishes a dominance hierarchy for breeding privileges. Usually the older rams in peak physical condition have the largest horns. They can often establish their dominance without having to fight to prove it. The famous head clashing battles are quite rare, but when two evenly matched rams cannot settle a dispute by display, a fight may follow.

TRANSITION TO WINTER

Winter in the Badlands is a quiet time. Most animals either migrate or hibernate to avoid the harsh winds and sub-zero temperatures.

RATTLESNAKE DEN UNDERGROUND / CARRION BEETLE

Rattlesnakes spend the winter in underground communal dens.

Many small mammals, reptiles, and insects take advantage of the abandoned Prairie Dog burrows which are deep enough beneath the surface to prevent freezing. Several hundred snakes in each den is not uncommon.

Only occasionally do they become irritated enough with one another to strike, but the bite is rarely lethal.

Carrion Beetles also use the snake's den. Exactly why they are here, and what they are doing, remain a mystery.

Luckily for this thirsty beetle, the snakes do not appear to be hungry.

There are many lessons hidden within these chiseled canyons, lessons from the past and lessons for the future. In a time when wildlife is all too often declining, it's comforting to know that when given the opportunity, and a little help, wildlife can make a comeback. If we can ever learn how to avoid harming these wild creatures in the first place, we will have learned the most important lesson of all.

CONCLUSION

The Badlands are home to an abundant variety of wildlife that's well adapted to a life among the steep spires. Equally important is the mixed-grass prairie that has been preserved within this rugged landscape. We can all be thankful that there are a few remote places where nature has persisted, places just like the "BADLANDS."

I'm Marty Stouffer. Until next time, enjoy our WILD AMERICA!